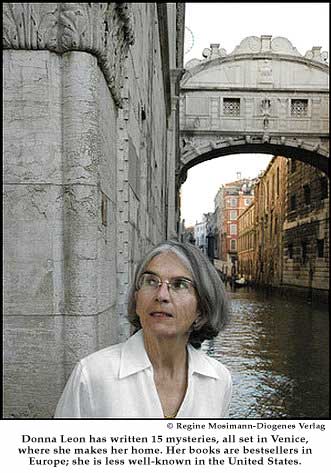

Then you look up and think: San Francesco di Paola! Didn't Tassini, the night watchman in "Through a Glass Darkly," live opposite the church of San Francesco di Paola? Didn't Brunetti walk down here from the Questura , the police station, to meet him in that bar that draws little swirling hearts with cappuccino foam? And just like that, you've entered the Venice of Donna Leon. As it happens, you've gotten a bit obsessed with Leon's Venetian mysteries ("Through a Glass Darkly," just published in the United States by Grove Atlantic, is her 15th). All feature Commissario Guido Brunetti, tenacious detective and devoted family man, whose unblinkered humanity you've come to admire. More to the point, perhaps, for someone with just a few days to spend here, reading Leon has fueled a fantasy common to visitors in this secretive, surreally beautiful city: that somehow, despite your total lack of local credentials, you'll be invited through what writer John Berendt calls "the invisible door" between the tourist's Venice and the one where actual Venetians live. Pretty to think so. Won't happen. But in Leon moments like this one, you come about as close as you're going to get. A minute ago you were an outsider with zero language skills and too little time. Now you're an intimate of Guido Brunetti, who has come to this very spot to meet a man who works in a glass factory (a fornace ) on the island of Murano. Something sinister is unfolding on the glassblowers' island that your good friend the commissario does not yet understand. Donna Leon's Venice is so popular in Europe, where her books are bestsellers, that specially organized tours bring fans from Austria, Germany and Switzerland to follow Commissario Brunetti's footsteps through the calles (lanes) and campos (public squares) of her adopted home. She's less well-known in the United States, but Grove Atlantic is working on that: It has brought her to Washington this week to commune with booksellers at the gargantuan annual publishing convention, BookExpo America. Venice is so much Leon's element, though, that you've been hoping to encounter her in it first. With luck, she'll make it back from a trip to Zurich in time. But in case she doesn't - - well, why not take a Brunetti tour? This one is given by Leon's old friend Toni Sepeda, another expatriate American with a home in Venice. The two met while teaching U.S. servicemen at European bases -- on contract with the University of Maryland -- which Sepeda still does but which Leon's writing career has rendered unnecessary. Sepeda is a diminutive, gray-haired Henry James fanatic with a completely un-James-like directness and an infectious energy belying her sixty-something years. She meets you in front of the reborn opera house, La Fenice, which seems doubly appropriate. Opera, even more than writing, is Leon's passion; the baroque orchestra II Complesso Barocco owes its existence in large part to her involvement and support. What's more, she introduced her detective series with "Death at La Fenice," in which Brunetti investigates the demise of a German conductor with a strong resemblance to the great but widely unbeloved Herbert von Karajan. "Everybody knows Venice is unique," Sepeda says, and, setting off from La Fenice toward Campo San Luca, she elaborates a bit. To lead one's whole life on foot, she says -- as the auto-free Venetians do -- "is so uncommon in the 21st century that we can't imagine it" without a native guide. She pauses, locates a relevant passage from that first book, then reads:

San Luca turns out to be what Sepeda calls a "talking campo" -- one of the prime gathering spots for Venice's fewer than 70,000 residents. "Everybody in the evening goes either to San Luca or to San Bartolomeo to stand around, pose and talk," she explains. Unlike more impatient foreigners, Americans in particular, "Italians can stand and lounge for an hour at a time just making idle chat. . . They're just gifted with that grace of ease, of just being, not really having to do. She points out Rosa Salva, Leon's favorite place to get a coffee and a brioche. (A Venetian, she says, is never without an opinion on the best place to buy something or the best route for getting across town.) Moving on to the church of San Salvador, which holds Titian's "Annunciation," she reads Leon's description of camera-wielding tourists and their rationalizations for interrupting whatever they find in progress there:

Actually, you'd love to see the famous painting yourself. But it's a Sunday morning, and you don't dare ask. Brunetti can be violently hostile to tourists, avoiding them when possible, shoving his way through them as necessary and always -- as Leon writes in one book -- "refusing to stop or in any way alter his course in order to allow them a photo opportunity." He gets his butt in a lot of snapshots as a result, but in his view, he's doing the foreign pests a favor: This was "probably the closest any of them would come to making contact with the city in any significant way." At Campo San Bartolomeo, she introduces one of Leon's great characters, Brunetti's wife:

Like Sepeda, Paola is a Henry James-loving academic. Unlike her, she has two kids at home. She's also smart, opinionated, reads at the table when eating alone, takes no guff from anyone and anchors Brunetti in the myriad subtle ways that good marriages -- a phenomenon rarely well-evoked in fiction -- often do. The family lives in a top floor apartment just off the Grand Canal, set back so as to be invisible from the street. It was constructed illegally, as Brunetti discovered after moving in. He lives in constant fear of the bribes he'll have to pay if the bureaucrats find out. A few blocks away, Sepeda turns down a quiet calle to point out Do Mori, one of the distinctive Venetian wine bars ( baccari ) that serve sandwiches and appetizers in tapas- like quantities. A venerable, narrow establishment with doors on either end, it is Brunetti's favorite and one of Sepeda's as well. Her longtime spouse-equivalent, Craig Manley, who's come along for the tour, has a story about their first Do Mori experience. They'd just befriended Leon, who had loaned them her apartment and said: You have to go to Do Mori. Splitting up to do some shopping, they'd arranged to meet there. "I was waiting for Toni and trying to be really cool," Manley says -- lingering and sipping his wine as he figured a real Venetian would do -- when in barreled six workers from a construction project nearby. "Roberto, the owner, just lined up their little ombre , their little glasses of red wine, and they just walked right in, shot them, and walked right through the other end," he says, laughing. "So much for lingering!" Sepeda says. It's not so easy, getting through that invisible door. A few minutes later, though, Sepeda ends the tour with a passage more generous to perpetually excluded visitors. It's from "Death and Judgment," a book dedicated to her and Manley, and as it begins, Leon's detective is headed for Piazza San Marco, the ultimate tourist destination:

"Well that's Brunetti," she says cheerfully. "And the rest of your day?" The rest of your day goes by in a haze of open-mouthed gaping and wonder-slowed steps. Every calle you wander down, it seems, ends in an archway through which some real Venetian's ancient home throws a burnt-orange reflection into a tranquil canal. The next morning, inspired by "Through a Glass Darkly," you head for Murano to watch the maestri , the master glassmakers, glide through their crowded workspace like dancers twirling molten glass. When you get back, you call Leon -- just off the train from Zurich -- and arrange to meet in a bar on Campo San Giovanni e Paolo. Here she comes now, across the bridge over the Rio dei Mendicanti, a fine-boned, silver-haired woman in black who looks as if she's lived here all her life. She hasn't. She was a New Jersey girl whose family had Irish, German and Spanish roots. After college she wrote advertising and hated it. In 1967, an Italian American friend invited her on a trip to Italy. She spent a couple of weeks in a tiny town in the south and thought: "My God, these people are so nice! This food is so good!" When she got to Venice, she wandered around for several days in "the equivalent of shock." Silly to ask why, but you do. "Unless you go out in nature and go for a walk in the Alps," Leon says, "there are few places where everything you see is beautiful." She didn't stay, though. She studied Jane Austen in grad school, then -- having been "born absolutely without ambition" and wanting nothing to do with tenure tracks -- headed out to see the world. She taught English in places like Iran, which she loved, and Saudi Arabia, which she emphatically did not. It wasn't until the early 1980s when, University of Maryland job in hand, she settled in Venice for good. Leon is a woman who knows her mind. She hates television, won't have one in her home and once put a neighbor who played her TV too loud in one of her mysteries just so she could kill her off. She ended a relationship with her first American publisher, HarperCollins, because she hated the vulgar covers it was producing. On a more positive note, she adores the historical fiction of Patrick O'Brian. "Ohhh -- he's God," she says when O'Brian's name comes up. She doesn't know where her own characters come from. One time she got to a point in a book "where Brunetti was doing something and someone knocked on the door. And it was a beautiful spring day and I didn't have a clue as to who was at the door. So I turned off the computer and I went for a walk." She walked for two hours. When she turned on her computer, in came Signorina Elettra -- the amazingly competent assistant to Brunetti's worthless, conceited boss. "She's delicious, I love her," Leon says. "Because I never know what she's going to do!" Signorina Elettra mesmerizes men, Brunetti among them, with her beauty, her out-of-the-box problem-solving techniques and her impenetrable reserve. His wife has the antennae to pick this up, and the wisdom, in the long run, not to be threatened. Leon is good with parent-child dynamics, too, and it makes you wonder: How can a childless, single woman write so subtly about family life? She credits her family of origin. "We talked to one another," she says. "We read, we talked -- I think we were reasonably happy people. It wasn't until later in life that I realized how unfashionable that is." Happy she may be, but she's not blind. She sees the real Venice sinking in a sea of tourism, with the waters rising every year. "One way to show the way things have changed would be to take a walk up Strada Nuova," she says. A few weeks ago, Venetian friends were cataloguing changes on that street. "This used to be, and now it is. . . "they'd say, naming the shops that have disappeared. "The man who used to make homemade pasta is gone, and that's a cosmetics store. The little couple who used to sell woven things from China, they're gone, and that's an imported jewelry store, little junk jewelry. . . The fruit store is gone, the bread store is gone, the cheese store is gone." The new shops all cater to visitors "who walk up and down from the train station to San Marco," she says. And this is not to mention the palazzi being turned into hotels. Brunetti is getting more pessimistic book by book, she says. You want to talk longer, to hear more about her penetration of that invisible Venetian door. About her research technique, which is mainly to listen quietly, interjecting a question now and then, while Venetian friends talk of their Venetian lives: "Oh really? How much did the judge want? That's not a lot, is it? You got the permit, hey?" About her music, and the book she's just starting, and.. But the door's not open to you, and you're out of time. Outside the bar, in the campo, you say goodbye -- then one last Donna Leon moment occurs. You look around and think: San Giovanni e Paolo! By the Rio dei Mendicanti! Isn't that where the young American's body washed up that morning in "Death in a Strange Country"? The crime scene to which Brunetti had to hustle after that phone call dragged him from sleep? It's a place where even the commissario needed help from a more knowledgeable native - - in this case, the pilot of his police launch -- to chart the mysterious Venetian tides that had swept the American there. Home Page | Email | Site Search Contemporary Mysteries | Series | Non-Series Historical Mysteries | Ancient Rome | Middle Ages | Renaissance | 1800s Suspense/Thrillers | Action/Adventure | Literary Fiction | Non-Fiction Crime Series on DVD | Non-Italian Settings | Theme Views | Location Views | Author Index | Site Map | What's New Mystery Links | Waiting List © 2002-2017 italian-mysteries.com (The Mysteries Set in Italy Website) |

|||||

VENICE -- It's just another church in a city full of churches, and the name doesn't register at first. You're walking down the Via Garibaldi on a warm spring day, reveling in the street life on the unusually broad avenue and in the relative absence of tourists here in the outer reaches of the Castello district, where native Venetians still outnumber interlopers like you.

VENICE -- It's just another church in a city full of churches, and the name doesn't register at first. You're walking down the Via Garibaldi on a warm spring day, reveling in the street life on the unusually broad avenue and in the relative absence of tourists here in the outer reaches of the Castello district, where native Venetians still outnumber interlopers like you.